Updated August 9, 2021

What are your brand’s stories? #ApostrophesMatter

One of the more controversial topics in marketing is how much control any company has in its “brand.” On one side of the argument are those who say brand control is an illusion. The thinking here is that not only do you not have control over how your brand is currently perceived, you never had any say in it.

Then there are the articles, services, templates, books, and other resources that aim to help companies build a strong and powerful brand identity. Whether it’s seven principles, 11 steps, five proven ways, or how to build it in five days – it seems as if everyone has a take on how marketers can build a strong brand positioning.

Can both arguments be correct?

In my experience, they are. Marketers do set out to distinguish their brands and demonstrate that distinction through creative visuals, messages, voice, and the experiences they create for prospective customers.

But when there’s a conflict between what you say your brand stands for and in the experiences you create, you lose control of your brand perception.

In other words, you can create a slick logo, a tagline, and guidelines that aim to make set your brand apart. But if you fail to deliver with the content experiences you create, then consumers will distinguish the brand in their own way.

And, unfortunately, that way is not usually what you’d choose.

Nowhere does this phenomenon play a bigger role today than in content: the brand story and the brand’s stories. Yes, there is a difference.

You see, when marketing teams talk about telling a “brand story,” they’re usually discussing the story the brand’s leaders tell about the brand itself. And then they quickly run into a dead end.

But the brand story is different from the brand’s stories (#ApostrophesMatter), namely the content you create to support the brand.

The brand story is different from the experiences and #content we create. Those are the brand’s stories, says @Robert_Rose via @CMIContent. #Storytelling Click To TweetLet’s explore.

Enough about me – tell me a story about me

The first reason content marketers struggle with the brand’s stories is that the brand’s values usually aren’t anything that can be used as the foundation of the story. Setting aside the brand symbol/logo, taglines, and core visuals, you’re left with value statements that the company believes to be true about itself.

For example, look at a Nike brand value statement:

(Nike) brings inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world and if you have a body, you are an athlete.

That’s good stuff, and helpful if you’re trying to understand how the Nike brand sees itself in contrast to others that sell sportswear. But for a Nike content marketer looking to create a new experience within the brand, it’s as the old English proverb says: “Fine words butter no parsnips.” In short, the storyteller won’t find these words terribly helpful, because the ideal already is fulfilled. There’s no journey to take the customer on.

Brand values are what the company claims about itself. Importantly, they assume that people care (or believe) in those values. But a brand storyteller needs to create experiences that create, convince, or reinforce the notion that those beliefs are important. In order to establish brand values, you have to move nonbelievers to become believers in that value.

Put simply: The storyteller needs to establish the pre-value existence to build tension and make the audience care about the values in question. In the Nike example, the storyteller needs to bring a point of view on the world that makes acquiring inspiration and innovation a valuable thing for everyone.

The storyteller needs a point of view that establishes tension, says @robert_rose via @CMIContent. #Storytelling Click To TweetPolitics aside, Nike does this well in its Dream Crazy ad, giving the audience a satisfying story. Nike celebrates the athlete and supports it with a distinct point of view. (Whether you agree or not, the storytellers are supporting their brand with a tension-filled story.)

On the other hand, when Nike leaned too heavily on its brand value claim of being “proud of its American Heritage,” and failed to create a compelling narrative to support a shoe with the Betsy Ross version of the American flag, its effort failed.

In CMI’s storytelling workshops, I call this the “core truth” – what you want to help change by telling people this story.

The wonderful storytelling coach and messaging strategist Tamsen Webster calls this concept the “red thread”(which I love). When I asked her about it, she explained that the “red thread is the why behind your why.”

Ultimately, it’s a subtle but important difference. Your brand story says what you want people to believe, and your brand’s stories must demonstrate why it’s important for the audience to believe it.

Put simply, Nike wants you to believe that it brings inspiration and innovation to every athlete – and that everybody is an athlete. Its brand’s stories must then demonstrate, somehow, that everybody is an athlete and that athletes place an extraordinary value on both inspiration and innovation.

And that brings us to the second challenge of talking about the brand story.

Content is stories – not the brand

In almost all cases, content leaders have minimal or no control over what the overarching brand stands for. Changing the brand story is either well above your pay grade, or it’s been established for decades, or (and probably most importantly) it’s different in the minds of the consumer than it is on your mission statement page.

Marketers have minimal or no control over changing what the overarching brand stands for, says @Robert_Rose via @CMIContent. #Storytelling Click To TweetTake Facebook. I don’t mean to throw them under the bus because every company struggles with this from time to time. But the company is struggling to match how it desires to be seen (as a trusted source that helps empower people to build community) with how it is seen (as the least trusted social platform) by many.

Content experiences, behavior, and storytelling can help repair the disconnect. But the stories must come from that distinct point of view that helps the brand reclaim something it may have lost.

Facebook could take a page from Nike’s playbook. In the late 1990s when Nike was lambasted for abusive labor practices, it not only changed the way it did business, it also formed The Fair Labor Association, a nonprofit dedicated to telling the story and creating awareness of the issue.

Most of the time, storytellers can’t change the brand (nor do most storytellers have challenges the size of the ones facing Nike or Facebook). But they can – and should – aim to support the brand in its mission to either establish, bolster, or repair its current claim about itself.

For example, all the way back in 2012, I had the pleasure of interviewing Jonathan Mildenhall, then the vice president of advertising strategy and creative excellence at Coca-Cola. Even someone in his lofty position realized the limitations of changing the brand story (no apostrophe) when it came to content.

As we talked about creative excellence in marketing, he said there was no way he could change the brand story. The values weren’t going to change. The iconic bottle shape certainly wasn’t going to change. The logo wasn’t going to change. And the ingredients in the bottle weren’t going to change. But Jonathan told me:

We fully understand that we are still going to have to do promotions, price messaging, shopper bundles, traditional ads, etc. … that isn’t going away. But our (brand’s stories) are the way consumers understand the role and relevance of The Coca-Cola Company. We have to make sure that those ‘immediate stories’ are part of the larger brand story.

This is why a brand’s stories are critical. As storytellers, your role is to understand how to create many original stories that demonstrate why people should care (the why behind the why) about the promise of the overarching brand story.

For example, among LEGO’s brand values is that imagination is critical. It says:

(C)uriosity asks why and imagines explanations or possibilities. Playfulness asks what if and imagines how the ordinary becomes extraordinary, fantasy, or fiction. Dreaming it is a first step towards doing it.

When storytellers create a LEGO brand’s stories (such as The LEGO Movie) – they use that foundation to come up with universal truths (or points of view) that show the customer the value of reaching for those universal truths.

Imagine that The LEGO Movie was a story about a young, arrogant LEGO hero who is the star builder in a big city. Then, one day he gets lost and finds himself in a small LEGO town where he must learn humility and that friends and family are worth far more than the glory of winning at building.

That’s an interesting and fun story – and it also happens to be the story of the 2006 movie Cars. But it doesn’t sound like a LEGO story does it? No. Instead, The LEGO Movie is about Emmet – an average Joe hero. In fact, Emmet is so “average” that at the beginning of the movie, he really has no personality. He needs a step-by-step instruction book just to get his day going. The movie is about Emmet discovering self-identity, and how dreaming creatively about what could be – can actually save the world. That sounds like a LEGO story.

Now that you understand the differences between the brand story and the brand’s stories (#ApostrophesMatter), let’s look at how to structure and test those brand’s stories.

Pressure test for brand stories

As you’re working with your team to establish, bolster, or repair your brand’s stories, you may come to an idea from any number of places. The lightning of an idea may strike in the shower or while walking the dog. Or you might be inspired by an idea that comes out of your team’s latest brainstorming stand-up. Or you inherit a story because your company just acquired a brand with a digital magazine.

Whatever the genesis for the idea, you may want to pressure test it to see how deep you can take that story. Perhaps – it’s a simple performance that’s really just best served as a surface-level TikTok video or a funny anecdote. Or maybe it’s really a deeper education idea that could be explored in a series of webinars or a white paper. Or perhaps it’s truly a platform that you can build an entire emotional story around.

But how do you know?

Six years ago, my colleague Carla Johnson and I introduced the four archetypes of storytelling in our book Experiences, The 7th Era of Marketing.

I’ve since been working on modifying that model a bit – and one of the areas where we’ve seen some interesting progress is in developing our story architecture pyramid.

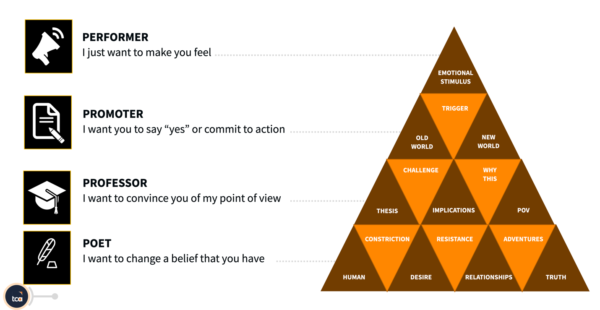

The story architecture pyramid encompasses attributes for each of the four archetypes. The simplest is the performer archetype. The only job of performer content is to make you feel something. It might be a joke, sad poem, or juggling act that amazes you. But if you can identify and deliver against the emotional stimulus – you have done your job.

At the other end of the spectrum, there is poet content. Here, at the bottom of the pyramid, there are seven attributes that we must identify and deliver to create a satisfying piece of content.

In my CMI University module on storytelling, I go into each one of these archetypes and break down the attributes and how you can pressure test against all of them to gauge where your story fits (if at all).

The key is to ask if your story has each of these attributes. For poet content, who is the human hero? What is their desire? What relationships do they maintain? What are their adventures? Check out the trailer for the LEGO movie and you’ll see answers for each of the poet attributes:

For professor content, what is your thesis? What is the universally recognized challenge, and what are the implications of both solving it, and not solving it? Why is THIS solution the best approach? Watch our documentary The Story of Content – and you can see these attributes are present.

Then there’s promoter content. What is the old world? What’s the trigger to making a change, and what’s the new world on the other side? This would be just about every 30-second ad you’ve ever seen.

Finally, there’s performer content. We just want you to feel something. There is probably no better quintessential example of this than the Sara McLachlan ASPCA commercial.

Here’s the thing: You already know what I’m talking about before I even go there.

FWIW, I can’t even watch this commercial because of the emotions attached to it:

When you are thinking through your idea for your brand’s stories, the question becomes how far down or up can you go. Spoiler alert: If you build poet content, going up to performer is easy. But starting at performer and going down to poet is exponentially harder.

But if you can fill it all in, you know you have a transcendent story that can align with your brand and goes a long way toward being a satisfying story for your audience.

Pressure test in action

Recently, I worked with an institutional financial services company on a new content mission for its digital magazine. The publication wasn’t working because the articles – coming from everywhere in the business – had no consistent value, theme, or point of view. The team wanted a clearly defined – and differentiating – story for the magazine. And, of course, the story needed to match the new brand the company was rolling out.

We worked through the answers to the seven components – hero, constriction, desire, relationships, resistance, adventures, truth. As you’ll see, the components are well detailed but not perfect. The team is using this to polish the mission for internal and external audiences.

- The human is the hero is today’s stressed financial advisor.

- The constriction is the increasing pressure to perform for clients and prove that expertise and ability to manage money are better than an algorithm.

- The desire is around these advisors needing and wanting continuing education. They don’t need more noise; they need unique perspective and guidance.

- The resistance in the advisor’s world is the danger of becoming automated by technology, algorithms, and artificial intelligence. It’s an atmosphere that increasingly devalues the human investor and makes trading more like gambling.

- The relationships are among expert portfolio managers, trusted colleagues, and genuine thought leaders in the industry financial advisors depend on in a network of talent to remain relevant to their clients.

- The adventures happen with practice management advice to news about the economy. We tackle everything that today’s financial advisor is challenged with.

- The truth is human investing is the only investing. It is a higher calling. New technology should be used, but it should be powered by wisdom. And only human advisors have this ability.

Can’t you see better stories, better posts, and overall differentiated value coming from that framework?

Further, you probably can start to see how you can now take the next step and extend it upward to the professor level – leveraging a thesis, challenge, and implications. Put simply, we can not only tell the emotional story of the financial advisor, we can teach them as well.

Now, to be clear, this framework is not a template. I see this in the way Christopher Vogler, author of The Writer’s Journey, describes Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey. As he writes, the hero’s journey “is not an invention, but an observation … a set of principles that govern the conduct of life and the world of storytelling the way physics and chemistry govern the physical world.”

In other words, not every great story has an earth-shattering, differentiating answer to every attribute in the story architecture. But the better the answers, the better chance you have something truly worth exploring. The framework can be a tool of expedience, getting to a better story more quickly. Or over a longer time, the framework might help develop a bigger and better brand story where none existed.

Not every great story has an earth-shattering, differentiating answer to every attribute in the story architecture, says @Robert_Rose via @CMIContent. #Storytelling Click To TweetI hope this framework becomes another tool in your skill box, helping you to become an amazing brand storyteller in a world that will increasingly value that talent.

Cover image by Joseph Kalinowski/Content Marketing Institute