Most of us know that achieving a viral hit is a crapshoot, even for the most skilled marketer. Your content is subject to the capricious, anarchic, unforgiving, cat-loving whims of the Internet. Yet, some still exploit meme culture to spread brand messages without understanding what it really means to “go viral.” [Face palm.]

So far, I’ve written this regular column on social media with barely a mention of the “v” word. Debunking the concept of viral content always seemed like too much of a slam dunk. How should I fill the remaining word count after stating the obvious in the first 100 or so words?

But strip away the myths and misconceptions of virality, and we may find a more useful truth worth exploring.

First, let’s get that slam dunk out of the way. Of course there is no foolproof method or secret formula for sending your content viral. If you think there is, I can point to hundreds of other pieces of content that use exactly the same techniques and go absolutely nowhere.

For a start, the whole concept is subjective. At what level do we say something is viral? A thousand views? A million? And over what time? Should we measure the number of shares, or is reach the metric to shoot for?

If there is no agreed measure, no benchmark, and no clear definition of what even qualifies as viral content – except after the fact – then it’s not much use in any serious discussion of marketing strategy.

Search vs. Social Media: How Audience ‘Intent’ Can Affect Content Marketing Performance

Except … let’s dig a little deeper.

The ‘amazing’ hashtag that wasn’t

The coal industry doesn’t have the best reputation right now. This is particularly true in Australia, where mining interests are lobbying hard to increase local coal production, despite global pressure to reduce carbon emissions.

In September 2015, the Minerals Council of Australia decided to repair coal’s reputation with a campaign – a hopelessly one-sided video, seeded in social media with the hashtag #coalisamazing. You can bet both went viral very quickly.

When the hashtag first appeared, I wasn’t the only one who thought it was satire. Before long, almost everything posted to the hashtag WAS satirical, lampooning the video, sharing anti-coal facts, and criticizing the industry. Within hours, a parody of the video spread quickly.

If the goal was for the video to go viral, gathering views and web traffic, then the campaign was a roaring success. But the content and hashtag had been repurposed to say the exact opposite of what was intended, fueling criticism instead of mollifying it.

‘Public relations fail of the year’ http://t.co/f3yDulpVAx #coalisamazing pic.twitter.com/LD4stAqfz5

— Greenpeace Aus Pac (@GreenpeaceAustP) September 7, 2015

Any controversial brand, industry, or topic needs to develop ideas and arguments that take the critics seriously. Persuasion is an art, not a hashtag.

You want your message to go viral, not the medium (apologies to Marshall McLuhan). So the message has to be palatable and persuasive enough to be adopted, adapted, and advocated by your audience.

There’s already a specific term to describe ideas that spread this way, one that predates viral by more than a decade – memes.

The meme epidemic

Today, when people talk about memes they usually mean captioned images or other content that people adapt and share in social media, usually for comic effect.

You’ve probably seen images of an exasperated Jean-Luc Picard, a passive aggressive Willy Wonka, or a million other images given new meaning with each new caption. I’m a big fan of the Hitler bunker videos. Since 2007, this meme has spawned thousands of variations, each adding new subtitles to a particular scene from the movie Downfall. The spoofs capture Hitler’s rage against everything from Xbox Live to Donald Trump’s election bid. The success of the Downfall meme is incredible when you think of the effort involved in producing each one.

Richard Dawkins coined the word “meme” in 1976 to describe the transmission of ideas or behaviors by imitation. But he’s not concerned with how the Internet has appropriated the word, as he told Wired magazine in 2013: “The meaning is not that far away from the original. It’s anything that goes viral. In the original introduction to the word meme in the last chapter of The Selfish Gene, I did actually use the metaphor of a virus. So when anybody talks about something going viral on the Internet, that is exactly what a meme is.”

If memes are viral by definition, constantly replicated, personalized, and redistributed through communities, does that mean marketers should develop branded memes instead of chasing viral hits?

Remember, the meme is the idea, not the adaptable content format. The original image, video, hashtag, etc., is just the medium that allows each person to express his or her own idea or message.

If I may borrow the Lord of the Rings’ Boromir meme for a moment, “One does not simply launch a branded meme generator. It is folly!”

Fresh in our memories

In April 1915, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corp (ANZAC) landed at Gallipoli as part of an allied campaign. By January 1916, more than 44,000 allied troops, including 11,410 Anzacs, were dead. Australia’s biggest military tragedy is marked by an annual public holiday and the Anzacs have become mythologized to almost sacred levels in Australian culture.

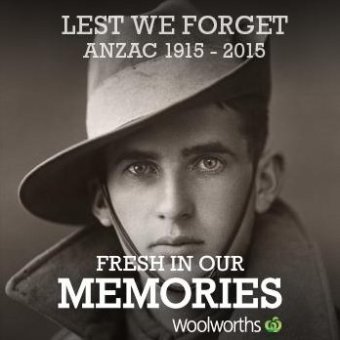

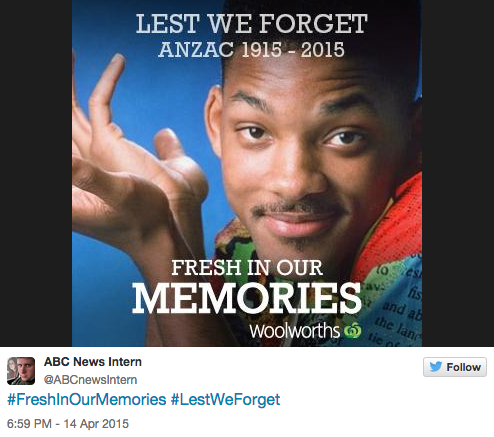

In April 2015, Woolworths – a supermarket chain and one of Australia’s largest retailers – decided to mark the centenary of the World War I Gallipoli campaign with a hashtag and meme generator. The campaign website invited people to commemorate Anzac Day with a custom profile picture or cover photo. “We encourage you to share a memory of someone you know who has been affected or lost to war, by changing your profile picture on social media to that person.”

If you uploaded an image of a relative who fought in the war, the website gave you a version optimized for social media, captioned with the words “Lest we forget, Anzac 1915-2015.” At the bottom of each image was a second caption – “Fresh in our memories” – and the Woolworths logo. It was this latter caption that sent the campaign viral for all the wrong reasons.

Woolworths’ tagline is “the fresh food people” and the word “fresh” appears throughout all of its marketing. Someone probably thought it was very clever to come up with a campaign tagline and hashtag with such strong brand alignment. But the wider community just saw a weak pun that placed war heroes on a par with iceberg lettuce.

People used the generator to make jokes, satirize local politics, and, above all, ridicule Woolworths. The news websites reported on the story within hours. Woolworths pleaded that it wasn’t a marketing campaign. “Like many heritage Australian companies, we were marking our respect for ANZAC and our veterans.” Unfortunately for Woolworths, the ill-advised branding meant the community heard – and shared – a very different message.

The Woolworths and the Minerals Council of Australia examples failed because they didn’t understand how the same sharing behaviors they wanted to exploit also could distort or undermine their message.

The moment you share a meme, you lose all control of how it may be used. So you’d better be sure your message will survive when you release it into the merciless wilds of social media.

This article originally appeared in the December issue of Chief Content Officer. Sign up to receive your free subscription to our bimonthly, print magazine. Find more best practices and rules of engagement for working with today’s top social media platforms. Read our Content Marketer’s Guide to Social Media Survival: 50+ Tips.

Cover image by Joseph Kalinowski/Content Marketing Institute