Updated: October 3, 2022

What’s your company’s most distinctive trait?

What’s the most important thing your company does?

What’s the main reason people should do business with your company?

Do you know? Does everyone in your company know? Do your organization’s blog posts, podcasts, videos, emails, and other communications convey the answers to these questions in one way or another day after day?

Consistency like that, believe it or not, is achievable. Maybe you think that your company is too big, too loosely structured, or too [fill in the blank]. Don’t throw up your hands. Tools exist that can help you bring your organization’s messaging into alignment. One such tool favored by many content strategists – a surprisingly simple but powerful tool – is the message architecture.

Why do you need a message architecture?

If you don’t have a message architecture in place, you’re missing out on something of value. Creating content without a message architecture is like building a house without a floor plan. Katie Del Angel shared other metaphors with me:

A clearly articulated message architecture is my best friend. It’s a North Star that everyone on a project (internal and external) can work toward.

Margot Bloomstein says, “Content strategy is what makes content marketing effective,” and “driving that strategy is the message architecture.”

Kristina Halvorson puts it this way: Message architecture “ is where your content really begins.”

#Contentmarketing relies on #contentstrategy, which relies on message architecture via @mbloomstein Click To TweetWhat is message architecture?

A message architecture, sometimes called a messaging architecture or messaging framework, is a small set of words – terms, phrases, or statements – arranged hierarchically to convey an organization’s messaging priorities and communication goals. It helps people in all departments deliver consistent messages in all types of content.

It’s called an architecture because it acts “as scaffolding for your content, supporting and shaping the content you actually produce,” Erin Kissane writes in her book, The Elements of Content Strategy. When marketers say “messages” or “messaging,” they aren’t talking about customer-facing content; they’re talking about the general impression they want customers to take away from the content.

Messaging is not copy; it’s subtext.

So, while a message architecture consists of words, it doesn’t tell content creators what words to use. It tells them what messages their words (and images, etc.) should convey and the order of importance of those messages.

While a message architecture should align with the corporate vision, mission, and brand values, it’s not the same as any of those things. It has three distinguishing qualities (as noted in Margot’s book, Content Strategy at Work):

- It conveys levels of priority.

- It’s actionable (in that it directly informs content decisions).

- It’s specific to communication.

What does a message architecture look like?

Message architectures can take various forms. Margot’s takes the form of a set of “prioritized brand attributes that stem from a shared vocabulary.” Her typical message architecture is “a concise outline of … attributes, each with sub-bullets that clarify meaning and add color.”

For example, the slide shown here is her interpretation of Apple’s message architecture. It shows that the company’s attributes are: 1. Confident but approachable (market leading, accessible), 2. Simple (clean, streamlined, unfussy, minimally detailed), 3. Inviting (friendly, supportive, not fawning).

Adapted from Margot Bloomstein’s presentation Be a Greedy Bastard: Use Content Strategy to Get What You Want, Slide 26

This example resembles a description of a corporate voice. Unlike most voice descriptions, though, this list is hierarchical – the elements appear in order of importance. Here, the top item in the hierarchy – “confident but approachable” – takes priority. This type of list tells content creators which attributes to emphasize when brainstorming blog topics, choosing words, sketching images, creating videos, crafting emails … you name it.

Margot gives a similarly structured example for a “stately financial institution.” The slide show’s the fictional company’s attributes and sub attributes as: 1. Respected (relevant, trusted), 2. Deep but narrow expertise (focused on large-cap funds), premium 3. Serving an exclusive class of investors.

Adapted from Margot Bloomstein, Term of the Week: Message Architecture

This example does more than the previous one. It conveys not only characteristics but also purpose. It’s a hybrid, telling us not just what this institution is like (respected, relevant, trusted – elements of voice, essentially) but also what it does: It focuses on large-cap funds and serves an exclusive class of investors.

Message architectures can go all the way in this direction, becoming architectures not of attributes but of statements – of messages, in fact. This approach to message architecture would complement a definition of voice rather than double as one.

Kristina Halvorson gives an example of that kind of message architecture for a content strategy consultancy.

The primary message is this: AwesomeCo solves the business problems behind the world’s most challenging web projects. Secondary messages include:

- We get things done.

- It’s not your project that’s the problem. It’s your business.

- We work with big organizations worldwide.

- We like our work complicated.

- The web is all we do.

- It all starts with a project.

Adapted from Kristina Halvorson, Message and Medium: Better Content by Design

If you used a two-tier architecture like this, you might want to further prioritize by putting secondary messages in order of importance. As Margot suggested to me in an email, prioritizing the secondary messages would make the architecture even more useful for resolving “conflicts of vision.”

Who wouldn’t love a tool that does that?

Margot and Kristina’s approaches aren’t the only ones out there. For example, in her book, The Content Strategy Toolkit, Meghan Casey describes what she calls a messaging framework, which builds on a core content strategy statement. Her messaging framework has three parts:

- First impression: What you want people to feel when they first encounter any piece of your content

- Value statement: What you want people to feel after spending a few minutes with any piece of your content because of what they now understand about your company

- Proof: How any piece of your content demonstrates that your company provides just what people need

Which form of message architecture should you choose? Here’s how Meghan answers that question in her book:

“It really doesn’t matter, as long as you adhere to the following:

- Make sure everyone who needs it has it.

- Actually use it to make decisions about content.

- Keep in mind that the messages are for you and the people in your organization who work on content.”

I especially like that middle bullet: Whichever form of message architecture you pick, it has to be one that your team will use.

What’s the value of a message architecture?

A message architecture’s value lies in its ability to clarify, for every content creator, the organization’s most important messages.

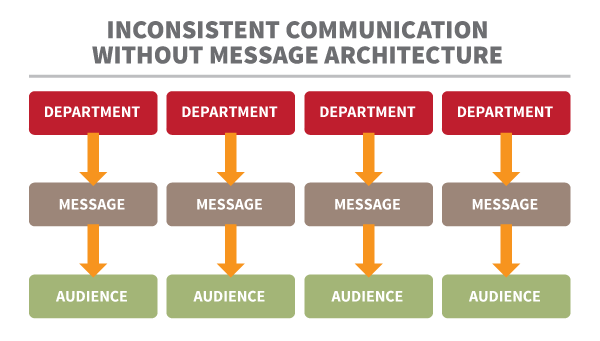

A message architecture scales beautifully, too, coming in as handy for a team of three as for a team of 3,000. As shown in the following two illustrations, a single message architecture can apply across all departments and all audiences.

The first illustration shows why communication without a message architecture leads to inconsistent messages – each department determines the message it wants to put out to a specific audience. The second illustration shows that a unified message architecture keeps the whole organization delivering the same messages to the appropriate audiences.

Adapted from Hilary Marsh, Managing the Politics of Content, Slides 37 and 38.

When an organization has no message architecture, its content teams working in departmental silos may create “a semi-schizophrenic brand experience” (to borrow a phrase from an email from Intel’s K. Scott Rosenberg). With a message architecture, organizations have a better chance of communicating consistently.

How can my organization create a message architecture?

There’s no right process for creating a message architecture. Since I’ve heard Margot talk through the card-sorting exercise she uses with her clients, I’ll describe that exercise here to give you one idea to try.

Here’s how the folks at Asana describe their experience with this type of exercise:

We were convinced. There was energy around our brand like never before.

Join the fun. Follow these seven steps.

1. Pick a leader.

Someone needs to lead the exercise. You may want to hire a consultant to facilitate. Alternatively, someone in-house could take the role. The leader must be capable of keeping participants aligned on the exercise’s purpose, which is not to select a handful of words but to reach agreement on the brand’s most important messages.

2. Prepare a set of adjective cards.

If your organization already settled on a set of adjectives that describe its corporate voice, you may want to simply write those adjectives on cards, have your stakeholders prioritize them, and skip to Step 5.

If your organization hasn’t defined its voice, or if you want to update your voice definition, follow all these steps. You’ll end up defining your corporate voice and prioritizing its elements to boot.

Create a set of cards, each with one adjective on it (a descriptive word or phrase) that might describe a brand – any brand: “innovative,” “traditional,” “edgy,” etc. The cards can be as simple as handwritten slips of paper. Margot’s card deck includes about 100 adjectives. Her set of adjectives – which you can also find on Page 30 of Content Strategy at Work – comprises terms she has heard across a range of companies and industries, including these types:

- Paired terms (“strategic” and “tactical”)

- Relative opposites (“traditional” and “modern”)

- Terms on a continuum (“assertive” and “aggressive”)

Photo courtesy of Margot Bloomstein

Here are some tips on selecting your adjectives. Unless otherwise noted, these tips come from this conversation and this conversation in the Content Strategy Google group.

- “Start with what you hear a lot, and a thesaurus. In general, I include a lot of terms that could be opposites (e.g., traditional and modern, strategic and tactical) as well as terms that represent shades of nuance on the same continuum (e.g., leading edge, cutting edge, bleeding edge). See Krista Stevens’ blog post for more details.” (Margot)

- Include words that the stakeholders have “already used in the past to describe their brand.” Also “cannibalize” your tone of voice and writing guidelines, and throw in “terms that have come up in user testing, design concepts, anything at all.” (Elizabeth McGuane)

- “We’ve been taking commonly used words like ‘funny,’ and trying to break them down further into more specific terms, like ‘cheeky,’ ‘witty,’ ‘tongue-in-cheek,’ for example.” (Aimee Cornell)

- If you use Margot’s terms, “pre-cull” those you think are most relevant and conducive to discussion in your group. (Sadia Latifi)

- Exclude terms that might be “distracting” or “potentially inflammatory” for that group. (Margot, Content Strategy at Work)

- Include terms that are “intentionally ambiguous to invite discourse.” (Margot, Content Strategy at Work)

3. Gather stakeholders in a room.

An effective message architecture depends on a shared vocabulary grounded in conversation; no one can go off and create message architecture alone. Invite everyone who needs to be involved in the decisions and everyone whose support will be needed.

4. Sort the cards.

Spread your cards on a table big enough that everyone can stand on the same side. Spend 45 to 60 minutes sorting the cards.

Separate the cards into three groups:

- Who we are

- Who we’re not

- Who we’d like to be

Photo courtesy of Margot Bloomstein

As you sort, encourage conversation, even friendly arguing. People need to “unpack their communication goals and dig into the buzzwords.” Explore why certain adjectives apply or don’t. Dig deep and “debate the nuances of each word.” Discuss what the adjectives mean in your corporate culture. (This is where the “shared vocabulary” comes in.)

Let me say all that in a different way: Treat the adjectives as springboards for conversation. The value of the terms on the cards doesn’t come from their inherent meaning; it comes from what the participants say about them. Write down what people say as they move the cards around. “The pauses, hesitation, and snap decisions are all worth noting,” Margot writes in Content Strategy at Work. Eventually, your message architecture must do more than transcribe the cards; it must capture the spirit of the conversation.

Say the group chooses “hip.” That choice in itself doesn’t tell you much. But say you overhear someone saying this about the term: “Everyone thinks we’re old and can’t react as quickly as the competition” (Content Strategy at Work). Now there’s an insight that could give content creators some guidance! You may eventually want to capture the gist of that comment – not just the adjective – in your message architecture.

When the cards are sorted into the three groups, turn your focus to the future group (who we’d like to be).

If you need multiple message architectures – maybe one for customer-facing content and another for internal communication – sort the future cards into natural groupings. For example, one group of terms might describe the way participants want potential customers to think about the company; another group of terms might describe the ideal corporate culture.

Finally, place the future cards –within their groups if you have more than one group– in priority order. (This is where the “architecture” comes in.) Why? Companies can’t communicate everything at once. Content creators need to know where to focus.

5. Document your message architecture.

Draft your message architecture. Keep it tight. (The three examples above use fewer than 60 words each.) Capture not just the adjectives people chose during the exercise but also the spirit of the ongoing conversation. As Margot says, “Words are valuable, but meaningless without context and priority.”

As you shape your message architecture, keep your mind open. A bulleted list may suffice, but you may want to go further. Experiment. Turn your words into a picture. Carve them in clay. Let the message architecture itself be your guide. Is “whimsical” your company’s top attribute? Stencil your message architecture’s elements on helium balloons, letting the most important one literally float to the top.

Send your message architecture to stakeholders for review. Revise it until people agree that you have your North Star. (Star-shaped balloons, anyone?)

6. Distribute your message architecture.

Share the message architecture with all who create and maintain your company’s content.

7. Keep communicating.

Creating a message architecture doesn’t ensure that people will use it. Follow up to keep the team in sync – a task that Carrie Hane Dennison calls strategic nagging. Even the most gung-ho professionals need reminders of what they’re doing and why.

For more on this card-sorting exercise, see these two books:

- Margot Bloomstein, Content Strategy at Work (Chapter 2)

- Meghan Casey, The Content Strategy Toolkit (pp. 195–197)

Start building your message foundation

“I start nearly every engagement by helping my clients develop a message architecture,” Margot shared with me. “It’s a simple deliverable that serves as the foundation for all our subsequent tactical decisions and activities.”

Message architecture. Simple. Foundational. Useful. And – if approached with an open spirit – fun. What more can we ask of any tool? Give this one a try. Let us know how it works for you.

Cover image by Joseph Kalinowski/Content Marketing Institute